The Creed – The profession Of Faith

Originally the Creed, the public profession of faith, was, as it still is, part of the mystery of Baptism. During Lent the candidates ‘preparing for enlightenment’ received their final intensive preparation for baptism, which took place on Holy Saturday during the reading of the Old Testament prophecies. In order to understand our present way of doing things it may be helpful to say a little about the history of the opening ceremonies of Baptism.

The Orthodox Baptistery in Ravenna. 5th Century

BAPTISM – MAKING A CATECHUMEN

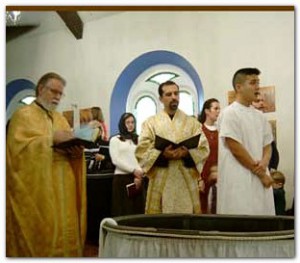

These ceremonies all presuppose that the candidate is an adult, who will have been under instruction for a number of years. It was quite common in the early Church even for people from Christian families to wait until they were thirty years old, the age of Our Lord at his baptism, before being baptised. The candidate will have a Sponsor, or Godparent, who will have to testify to the Bishop that the candidate is leading a moral life and is worthy of Baptism. Baptisms normally took place at Pascha, during the great vigil on Holy Saturday night. This is the service that we now celebrate on Holy Saturday morning.

Mosaic in the Dome of the Orthodox Baptistery in Ravenna

In our present books the beginning of the ceremonies of Baptism have the title, ‘The Making of a Catechumen’. This really only describes the first prayer of the ceremony. The exorcisms that follow are those that were given to the catechumens during Lent when they received their final instructions in the Faith. What follows is a description of the ceremonies in the Great Church in Constantinople over a thousand years ago. At midday on Good Friday, the candidates are brought to the Patriarch in the Great Church. He instructs the catechumens to undress and remove their shoes and then explains the importance of what is to take place. He begins, ‘The end of your instruction has arrived: the moment of your redemption. Today you are about to present Christ with your contract of faith. Paper, ink and pen are conscience, tongue and behaviour. Take care then how you write your confession’. The candidates are to renounce the devil and commit their lives to Christ for ever. The Patriarch explains why the candidates are to turn to the west to renounce Satan, ‘The devil is now standing in the west, grinding his teeth, tearing his hair, wringing his hands, biting his lips, crazed, bewailing his loneliness, not believing in your liberation. And therefore Christ sets you before him, so that, having renounced him and blown on him, you may take up the war against him. The devil stands in the west, where darkness begins. Renounce him and blow on him, then turn to the east and commit yourself to Christ’.

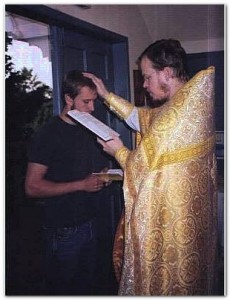

‘Inscribe him in your book of life’

Then follow the renunciation of Satan and the commitment to Christ, during which the Patriarch entrusts them with the Creed. In this old rite it is the Patriarch who first says the Creed and the candidates repeat it after him. This is done three times. It is the Paradosis, the Tradition, the ‘handing on’ of the Faith. We do not invent the faith for ourselves, we receive what has been handed down from Christ through the Apostles, and we, in our turn, hand it on to those who come after us. St Paul insists on this in his first letter to the Corinthians. Writing about the Lord’s Supper he says, ‘I received from the Lord what I also handed over to you, that the Lord Jesus, on the night he was handed over, took bread’. Later in the same letter he writes, ‘For I handed over to you in the first place what I received, that Christ died for our sins in accordance with scriptures and that he was buried and that he rose on the third day in accordance with the scriptures’. Already in St Paul we find phrases that will be incorporated into the Creed that we say today.

In the earliest rites we have this profession of the faith took the form of questions that the priest asked the candidate before each of the three immersions. Here is one early description of baptism. ‘When each person to be baptized has gone down into the water, the one baptizing shall lay hands on each of them, asking, “Do you believe in God the Father Almighty?” And the one being baptized shall answer, “I believe.” He shall then baptize each of them once, laying his hand on the head of each one. Then he shall ask, “Do you believe in Jesus Christ, the Son of God, who was born of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary, who was crucified under Pontius Pilate, and died, and rose on the third day living from the dead, and ascended into heaven, and sat down at the right hand of the Father, the one coming to judge the living and the dead?” When each has answered, “I believe,” he shall baptize a second time. Then he shall ask, “Do you believe in the Holy Spirit and the Holy Church and the resurrection of the flesh?” Then each being baptized shall answer, “I believe.” And thus let him baptize the third time.’

‘That there may come down upon these waters the cleansing operation of the Trinity’

From this description it is easy to see that the basic Christian profession of faith is threefold. We ‘confess Father, Son and Holy Spirit, Trinity consubstantial and undivided’, as we sing just before the Creed in the Liturgy. Some books divide the Creed into twelve ‘articles’, one for each of the Apostles, but this is not strictly correct. We are not asked if we believe in, say, the resurrection, but ‘in Jesus Christ, who, among other things, rose from the dead’.

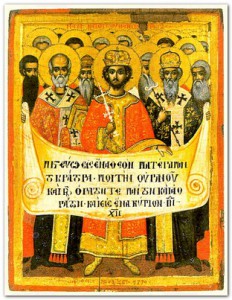

Icon of the First Council of Nicea, 325

Note that the icon painter has, mistakenly, used the singular, ‘I believe‘

Until the First Council of Nicea in 325 the various churches had their own formulas for use at baptisms. One such formula is an old Roman one, known as the Apostles’ Creed, and which is still used in many western churches alongside the only universal Creed, the Creed of Nicea as proclaimed at the Council of Constantinople in 381 and confirmed at Chalcedon in 451. The Fathers of the Councils proclaimed the Creed together and began, ‘We believe’, but in the Liturgy we keep the old baptismal form, ‘I believe’, to remind us of our baptism and of our solemn commitment to Christ, a commitment that we must renew day by day.

During the fourth and fifth centuries there were many debates and controversies about the faith, about the Holy Trinity and the person of Our Lord, and this led some churches in the East to introduce the practice of proclaiming the Creed during the Liturgy. This was introduced in Constantinople in about 518. In Rome it was only introduced in 1014. Why is the Creed proclaimed at this particular moment in the service? The most likely reason is that it was felt that it should be said until the catechumens had been dismissed. It was only after they had been baptised that they would allowed to proclaim the Creed in public alongside their Christian brothers and sisters, with whom they had just exchanged the Kiss of Peace.

Finally here are one or two remarks on particular words and phrases in the official translation of the Archdiocese. At the First Council of Nicea the Fathers defined that the Son was not inferior to the Father, that his ‘being’, ‘essence’, or ‘substance’; that he was as much ‘God’ as the Father. They expressed this by using a word not found in the Bible, homoousios, because the heretics managed to twist all the words in the Gospel to make Christ inferior to the Father. There is an amusing account by St Athanasios of the Council of Nicea in which he says that every time the Orthodox suggested a suitable word from the Bible, the heretics got into a huddle and came up with a heretical way of understanding it. So finally the Orthodox proposed a word which, though not in the Bible, would express the true faith. The word homoousios means ‘of the same essence’, of the same being’, but it is not an explanation. We can never understand the supreme mystery of God, the Holy Trinity. The word is really a sort of marker. If you are prepared to say that the Son is homoousios with the Father, then you are Orthodox; if not you are not. The earliest Latin translations used the word ‘consubstantial’. We decided to keep this to underline the fact that we cannot have an ‘explanation’ of the Trinity.

‘For our sake …….he became man’. The more important point here is the second part. Many English versions have ‘and was made man’. This is a mistranslation of the Latin and misrepresents the Greek, which means ‘he became a human being’.

‘He is coming again’. Most English versions have the future ‘He will come again’. The Greek has a present, ‘coming’. The Lord’s coming is not something in the remote future. It is always immediate, always imminent. One could even say it is always a threat, since our Lord himself compares it to a burglar who comes unexpectedly night.

‘Together glorified’. Most English versions simply have ‘glorified’. But the Greek word syndoxasmenon is very uncommon and was used by the Fathers to underline our belief that the Holy Spirit is as truly God as the Father and the Son.

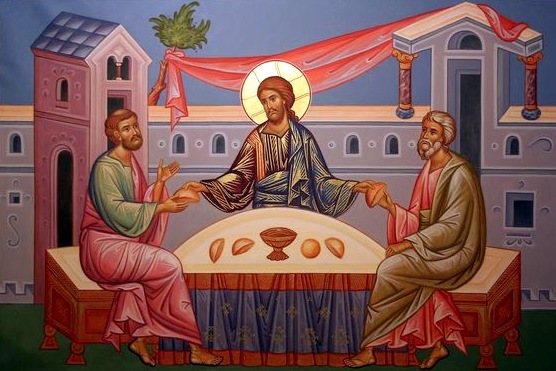

Now that we have proclaimed our Faith in the Most Holy Trinity we are ready to begin the most solemn part of the Liturgy, the great prayer of thanksgiving and the Mystical Supper of the Body and Blood of Our Lord and Saviour.