The Liturgy Of The Word

‘Holy God. Holy Strong. Holy Immortal’

As the clergy enter the Altar, the singers chant the hymns appointed for the day. On most Sundays these consist of the Apolytikion of the Resurrection, that of Dedication of the Church and the Kontakion of the season. On ordinary Sundays we sing the Kontakion of the Mother of God, ‘Protection of Christians’, but before and after the great feasts we sing their special kontakia. For example, from 27 July until 13 August we sing the kontakion of the Transfiguration. Ideally the people should join in singing these hymns, most of which are well-known and set to simple tunes. The singers are there to lead the people of God in singing; they should not usurp the people’s part in the service. There are places in the Liturgy where more elaborate music is called for, such as the Cherubic Hymn, but the people should be encouraged to sing the simpler hymns and responses, not discouraged by glares from the psalterion if they join in, as sometimes happens. When a Bishop celebrates he censes the Altar, the icons and the people at this point, to mark the beginning of the Liturgy proper.

After the hymns for the day have been sung there comes the solemn singing of the Trisagion, thrice-holy hymn to the Most Holy Trinity, ‘Holy God, Holy Strong, Holy Immortal, have mercy on us’. This is one of the most important and oldest of our Orthodox hymns and is said near the beginning and end of almost every service. It forms the last part of the Great Doxology and should be part of every Orthodox Christian’s morning and evening prayers. It is even sung in Greek and Latin on Holy Friday in the Roman Catholic Church, and forms part of their prayers for the dying. In our Orthodox tradition it is understood as a hymn to the Most Holy Trinity and so it is quite incorrect to put the word ‘and’ into the second and third phrases, as some English translations do.

The triple and double candles

symbolise

the Holy Trinity

and

the two natures of Christ

Saint John of Damascus wrote a whole treatise explaining the meaning of the hymn, and his teaching is summed up in a hymn written by the Emperor Leo the Wise for the feast of Pentecost, which we still sing at Vespers on that day. ‘Come, you peoples, let us worship the Godhead in three persons, the Son in the Father, with the Holy Spirit. For the Father timelessly begot the Son, co-eternal and co-reigning, and the Holy Spirit was in the Father, glorified with the Son; one power, one essence, one Godhead, whom we all worship as we say: Holy God, who created all things through the Son, with the co-operation of the Holy Spirit. Holy Strong, through whom we have come to know the Father, and through whom the Holy Spirit came into the world. Holy Immortal, the Advocate Spirit, who proceeds from the Father and rests in the Son. Holy Trinity, glory to you!’

Bishop’s throne, with synthronon

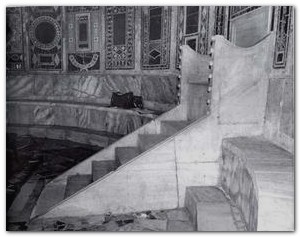

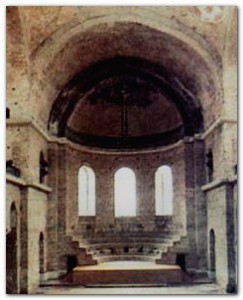

During the Trisagion the clergy should take their places behind the Holy Table at the Synthronon, that is the row of seats in the apse, either side of the Bishop’s throne, to listen to the readings. Sadly many modern church buildings do not have a throne or a synthronon behind the holy Table. A notable exception in London is the cathedral of Agia Sophia.

Sythronon of agia eirene in constantinople

What people now think of as the Bishop’s throne next to the psalterion was originally his stasidion, or choir stall, where he stood for the offices, like Vespers and Matins. In monasteries it is still the Abbot’s stall, where he stands on great feasts. When Bishop celebrates the Trisagion is much elaborated, involving a solemn blessing of the people by the Bishop and leading into the chanting of the titles of the Patriarch and Bishop and wishing them ‘Many Years!’

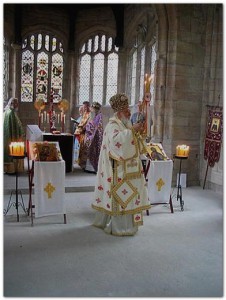

Blessing by the bishop at the Trisagion

‘Lord, Lord, look down from heaven and see

and visit this vine, which your right hand has planted’

During the Trisagion the Reader should come and receive the blessing of the celebrant to read the Apostle. He should then go to the centre of the church and face East to proclaim the Psalm and the Apostle. In the old days there were at least three readings at the Liturgy, from the Old Testament, the Apostle and the Gospel. Between the first two a Psalm was chanted with one verse repeated as a refrain. In the Orthodox Church today the first reading has disappeared and the psalm has been reduced to the refrain, known as the Prokeimenon, and a single verse of the Psalm. In the old days the Reader announced both the Tone to which the Prokeimenon should be sung and the number of the Psalm. It is good to see that the latest service books from Athens encourage the restoration of this custom.

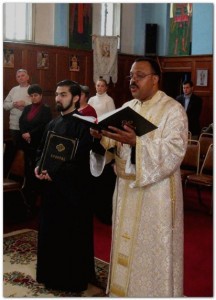

reading of the apostle at a Romanian liturgy

(in two languages)

After the prokeimenon the Reader declaims the Apostle from the centre of the church, the Priest or Deacon having first urged the people to pay attention, ‘Let us attend’. It is, after all, the word of God that is being proclaimed. In Orthodox tradition the readings from Scripture are always chanted, not simply read. This is for two reasons. The first is to make sure they are audible. In most of our churches there is no need for microphones. There were none in the churches of Constantinople in the days of the Emperor Justinian, and Agia Sophia is, to put it mildly, somewhat larger than most of our present buildings. The second reason is because the Reader is simply a transmitter, it is not up to him to put his own slant on the text, to put himself, as it were, between God and the listener. It is God’s word that we have come to hear, and not the reader’s, be he Bishop, Priest, Deacon or Layman. They are simply loud speakers, not the authors.

During the course of the year the Church reads the writings of the Apostles in the order in which they come in the New Testament. We start at Pascha with the Acts of Apostles, which tells how the Good News of the Resurrection travelled from Jerusalem to Rome itself, the centre of the Empire. After Pentecost we read from the Epistles of St Paul, more or less in order of length, then those of the other Apostles, St James, St Peter, St John and St Jude. This takes us to the beginning of Lent, during which we read the Epistle to the Hebrews. The Apocalypse of St John is never read liturgically.

After the Apostle the Reader should once again get the Priest’s blessing while the Singers begin the ‘Alleluia’. This should be properly sung, together with its accompanying verses, so that there is time to cense the Gospel book, the icons and the people and for the Deacon to make his way to the Ambo to chant the Gospel. The censing and the singing of the ‘Alleluia’ have been associated with the proclamation of the Gospel since very early days in both East and West. Censing during the chanting of the Apostle is not a good idea. If we have been told to ‘pay attention’, we want to be able to listen and not to be distracted by the rattling of chains and the tinkling of bells.

deacon proclaiming the holy gospel

(in two languages)

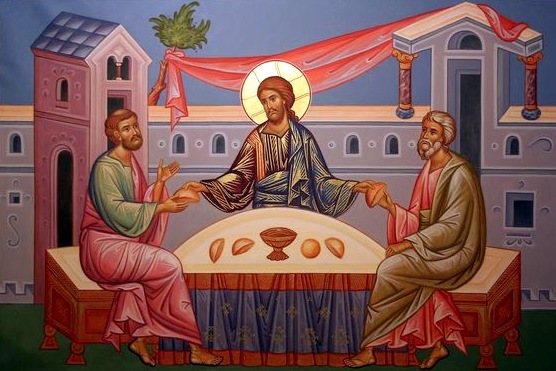

The solemn proclamation of the Gospel is the high point of the first part of the Liturgy. As Christ, the Word of God, explained the Scriptures to the disciples on the road to Emmaus, so he comes to us now in the words of the holy Gospel, which symbolises his presence among us. To hear the Gospel is an honour, a privilege. At Matins the priest says, ‘And that we may be counted worthy to listen to the holy Gospel, let us pray to the Lord God’. This is why we are invited to ‘stand upright’ and to ‘listen to’, or to ‘hear’, the Holy Gospel. In Greek the word to ‘hear’, akouein, is related to that for to ‘obey’, ypakouein. As Jesus says to the woman in the crowd, ‘Blessed are those who hear the word of God and keep it’. ‘Hearing’, ‘listening’, is one thing; doing something about it is another. Our immediate response, as so often in the Gospels themselves, is to give glory to God, ‘Glory to you, Lord! Glory to you!’. The priest blesses us with the holy Gospel, the icon and sign of Christ, the Incarnate Word, and replaces it on the holy Table.

The Gospel is not always easy to understand, nor is it always easy to put it into practice, and so, since the very earliest days of the Church, the reading of the Gospel has been followed by the sermon. In the earliest description we have of the Liturgy, written by St Justin the Martyr around 150 AD, we read, ‘And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the Apostles or the writings of the Prophets are read, as long as time permits. Then, when the reader has ceased, the President verbally instructs, and exhorts us to the imitation of these good things’. One can only conclude that the Orthodox Christians in the second century arrived for Liturgy somewhat earlier than their descendants of the twenty first.